Emma Sky discusses her new book, The Unraveling, as well as ways to fix Iraq and defeat ISIS.

- How Wars Are Fought Again in Memory

- A Double Dose of Reality on “Homegrown Terrorism”

- How the World Stopped Worrying about Nuclear Disarmament and Forgot about the Bomb

- The Soldier Who Named it Burkina Faso

- Leaders in Transition

- Was Machiavelli Right About Innovation?

- As the Smoke Clears: Tobacco and the US Military

- ISIS Is an Existential Threat, but Not to the West

- A Shattered and Dangerous Land

- War Is Extinct, and We Miss It! Part 3: What Is Our Military Future?

- War Is Extinct, and We Miss It! Part 2: Why Do We Miss War?

- War Is Extinct, and We Miss It! Part 1: What Happened to War?

- Why Are God, Jehovah and Allah Taking All the Blame?

- Women in Combat: Why Now, What’s Next

- The War Aquatic with Nancy Sherman

- Why Are the Religions of the West so Violent?

- The Islamic State Meets the Laws of Economics

- Winning the Peace in Mesopotamia

- A New Image for an Old al-Qaeda

- The Taliban’s Siege of Kunduz Highlights a Worrying New Dynamic

- Let’s Make ISIS a State

- Women in Combat Part 3: Are Women the New Blacks?

- Women in Combat Part 2: Reality

- What’s Haunting Anglo-Iranian Relations

- Going Public: The New Importance of Saudi-Israeli Rapprochement

- Why NATO Intervened in Libya, but Not Syria

- Why Britain hasn’t Followed the US into Syria

- NATO Has Little to Show from its Libya Intervention

- Women in Combat: Can versus Should

- In Iraq, Where There is No Will, There is No Way

- Enemy’s Enemy: Who is Giving America Intel on ISIS in Afghanistan?

- Fiction for the Strategist

- To Catch a Cheat: Trusting the Verification Regime in Iran

- Disarming the Profession of Arms: Why Disarm Servicemembers on Bases?

- Death by Treasury: The Challenge of Defense Austerity in Britain

- Figure Out the Air Force: Airpower, Nuclear Weapons and Next Generation Bombers

- 200 Years after Waterloo, How will Today’s Wars be Remembered?

- Here’s How We Should Think about Intervention

- Why We Don’t Need a New War Against ISIS

- The Fight Within Every Veteran and with Those They Love

- Challenge 2016 Candidates on Long-Term Security Policy

- Vladislav Surkov: The (Gray) Cardinal of the Kremlin

- Is Clausewitz Still Relevant?

- Whack-a-Mole Strategy Against ISIS not Working

- Emma Sky on How to Fix Iraq and Defeat ISIS

- ‘Signature Strikes’ by Drones Are Counterproductive

- The Melting Pot of our Military

- Where’s the Courage of our China Conviction?

- John Boyd’s Revenge

- Should Women Fight Alongside U.S. Special Forces?

- Want to Save the Defense Budget? Kick Those Nasty Habits

- Urban Warfare and Jade Helm: Why We Should Invade Texas

- Thanassis Cambanis on Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution

- Destroy the ‘State’ in Islamic State

- Meeting the Unforeseen: The Need for More Military-Industrial Analysis

- Are We at our Norman Angell Moment with China?

- How to Avoid Future Hadithas

- Time to Squeeze Iran Harder

- America Needs an Open Source Intelligence Fusion Center

- Two Sides of the Vietnam War and its Personal Costs

- Simple Rules and Tools for Modern Leadership

- A Bitter Pill: Fake Drugs and Global Health Security

- UK General Election: ‘There Are No Votes in Defence’

- The NFL’s Phony Patriotism

- Is Afghanistan Turning a Corner?

- House of Cards: How King Salman’s Reshuffling May Backfire

- Fixing Military Intelligence Gathering, but of the Medical Kind

- Iran is no Irrational ‘Martyr State’

- The Battle for Bayji, and the Heart of Iraq’s Oil Industry

- This Week in War

- From Tikrit to Mosul

- Reports of Assad’s (Pending) Demise May be Greatly Exaggerated

- Special Relationship: U.S. Marines Flying from a UK Warship

- America’s Failed Revolution

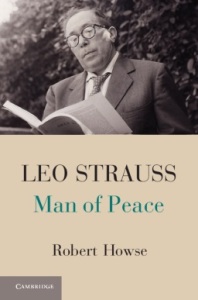

Leo Strauss: Teacher, Philosopher, ‘Man of Peace’?

By The Editors

Leo Strauss is known to many people as a thinker of the right, who inspired hawkish views on national security and perhaps even advocated war without limits. Robert Howse provides the first comprehensive analysis of Strauss’s writings on political violence, considering also what he taught in the classroom on this subject. Strauss emerges as a man of peace, favorably disposed to international law and skeptical of imperialism – a critic of radical ideologies (right and left) who warns of the dangers to free thought and civil society when philosophers and intellectuals ally themselves with movements that advocate violence.

So, first things first. According to Seymour Hersh, among others, Leo Strauss famously inspired members of the George W Bush administration like Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Abram Shulsky in their political thought. Wolfowitz and Shulsky, among other neoconservatives, studied under Strauss at the University of Chicago, where he developed quite a following, a sect even. Strauss is the father of the neoconservative movement. Right?

No. Quite the opposite. Strauss taught the inherent superiority of peace to war, the folly of trying to impose one political model, whether liberal democracy or something else, on the entire world, and he held that a healthy society is based on trust and openness about the grounds of political decisions, not the deception of the public by their leaders. None of them — Wolfowitz, Perle, or Shulsky — had much to do with Strauss himself.

Wolfowitz’s real teacher at Chicago was Albert Wohlstetter, a Dr. Strangelove-type figure who played around with the idea of trying to win a nuclear war, something that Strauss said was contrary to all common sense. Perle also was influenced by Wohlstetter. So Hersh and company got their intellectual history largely wrong. Much has been made of the connection of these men to Allan Bloom, a leading student of Strauss; Wolfowitz and Shulsky were charmed by Bloom as undergraduates at Cornell’s elite Telluride House. Bloom, whom I happened to know personally as a young man, was a compulsive name dropper, who liked to associate himself with the powerful or famous. He played up his connections to Wolfowitz, who became a neocon high flyer in the Reagan era. This has nothing to do with Strauss, who to use his own words, shunned the limelight because he was seeking the light. How Bloom may have distorted Strauss’s thought to prepare the ground for neoconservatism is a long story, which I touch upon in my book.

Wolfowitz’s real teacher at Chicago was Albert Wohlstetter, a Dr. Strangelove-type figure who played around with the idea of trying to win a nuclear war, something that Strauss said was contrary to all common sense. Perle also was influenced by Wohlstetter. So Hersh and company got their intellectual history largely wrong. Much has been made of the connection of these men to Allan Bloom, a leading student of Strauss; Wolfowitz and Shulsky were charmed by Bloom as undergraduates at Cornell’s elite Telluride House. Bloom, whom I happened to know personally as a young man, was a compulsive name dropper, who liked to associate himself with the powerful or famous. He played up his connections to Wolfowitz, who became a neocon high flyer in the Reagan era. This has nothing to do with Strauss, who to use his own words, shunned the limelight because he was seeking the light. How Bloom may have distorted Strauss’s thought to prepare the ground for neoconservatism is a long story, which I touch upon in my book.

If Strauss pointed out the tensions and vulnerabilities of liberalism and liberal society it was to warn of dangers and vulnerabilities, not to pave the way for neoconservatism. The way he put it was something like this: being a friend of liberalism means one must not be a flatterer. During the Cold War, Strauss maintained a hard line position against Soviet communism. In the US that meant that he seemed like a natural ally of a certain kind of conservatives (even if he criticized harshly McCarthy and McCarthyism). But as one appreciates if one knows something of European political and intellectual history, anti-Sovietism could well be a position compatible with being a progressive, a social democrat. Strauss also challenged what might be called highly optimistic narratives of human progress-he was sceptical that technology could solve fundamental human problems, and underlined that it had created others, most notably the risk of nuclear catastrophe. This questioning of progress also in a sense make him an ally of some forms of conservatism. But surely not of neoconservatism, which touts America’s ability to use its technological and military superiority to impose itself and its values on the world.

Critics of Strauss, such as Shadia Drury and Nicholas Xenos, have accused him of being an imperialist, militarist, and elitist, someone who believed the state must or should lie to the people because they must be led and, as one could read from Plato’s Republic, these white lies facilitate leadership. Your book calls him a “Man of Peace”, not of war, someone who preferred plurality of thought and debate, a man who believed philosophers should know politics, but not be politicians. Why is there such a wide range in the interpretations of what Strauss thought? Why is Strauss seemingly so misunderstood?

Strauss wrote philosophy in an unusual way, not by setting out his own views in a treatise but, most typically, by constructing what I call imagined inter-temporal dialogues between thinkers of different historical periods — “How would Thucydides respond to Machiavelli on the need to remove moral constraints in war?” — for example. Strauss vividly presents the competing positions of the different thinkers, and one needs to follow closely to see his own voice of judgment and critique emerge from the fray. If one starts, based on erroneous intellectual history, with the idea that Strauss is directly associated with warmongering, imperialism, tyranny, etc., then it is easy to take the short cut and pull out passages where Strauss is for example representing the ideas of Machiavelli or Nietzsche, and assume that he is presenting his own position.

This relates to a further misunderstanding. One of Strauss’s most original contributions to scholarship was articulating how thinkers in the past used the art of writing carefully or even deceptively to avoid persecution. He also argued that above all pre-modern writers had a valid concern that their ideas not be abused to undermine legitimate constitutional politics, and thus wrote subtly for that reason too. From this came the suspicion that Strauss himself was writing deceptively, with all kinds of nasty messages hidden in the words of people like Machiavelli and Carl Schmitt. But there is no reason to assume that what Strauss thought was true of thinkers facing persecution in previous centuries was true of himself, once he had gone to America.

If Strauss pointed out the tensions and vulnerabilities of liberalism and liberal society, it was to warn of dangers and vulnerabilities, not to pave the way for neoconservatism. The way he put it was something like this: Being a friend of liberalism means one must not be a flatterer.

A Strauss quote at the beginning of your book caught my eye: “It should go without saying that a man of peace is not the same as a pacifist.” What did Strauss mean? Is it right to say Strauss found a friend in this publication’s namesake, Marcus Tullius Cicero? In reference to war and political violence, where did they come together and where did they part, if at all?

Strauss regarded Cicero, much like Hugo Grotius in early modern times, as adapting natural right or a morality of humanity to the realities of political life, including the realities of political violence, i.e. as a realistic humanist. That is how Strauss presents Cicero in one of his most famous books, Natural Right and History. This is the spirit in which Strauss himself writes about war.

This question fills entire books, but what did Leo Strauss think of war? When would Strauss see the use of force or violence as necessary or legitimate and when not?

Certainly for self-defense. Strauss believed that humanitarian intervention could be justified but stressed the great likelihood of it being abused. Thus, he was closer to liberals such as Anne Marie Slaughter and Samantha Power, who have argued for intervention scrupulously targeted to specific humanitarian goals, rather than “take off the gloves” neocons like Bill Kristol. He saw a kind of false or limited nobility and even shreds of humanity in some forms of past imperialism, but was against its revival in the 20th century. On the other hand, he supported peaceful forms of transnational order, like the European Community (now the EU).

Recently, in an oped attacking President Obama’s foreign policy, Bill Kristol misused a famous quotation from Strauss: “The sorry spectacle of justice without a sword or of justice unable to use the sword.” But here Strauss was referring to the inability of the Weimar Republic to stop extremist violence within its borders. A very different thing than foreign relations. In fact, Strauss taught his students exactly the opposite of what Kristol implies, holding that, “foreign relations cannot be the domain of vindictive justice.” We must not base our policies on knee-jerk reactions of anger, even when we are greatly tried by those who treat innocent people, including our own nationals, with utmost brutality. Further, we must be aware of the limits of our power to solve every problem, whether with force or diplomacy.

I was reminded of Strauss when President Obama said, in his speech about ISIS earlier this month, “We cannot erase every trace of evil from the world.” Strauss wrote during the Cold War, “No bloody or unbloody change of society can eradicate…evil.” The similarity of the words and the sensibility is striking.

Turning to the headlines, America and NATO are currently juggling questions surrounding the possible use of force in Ukraine if it becomes necessary. What thoughts would Strauss have had or what can Strauss tell us on possibly using armed force to halt Russia?

He always supported a hard line against Soviet expansionism, and the protection of the self-determination of the threatened peoples. That would be the case today with Russia. But a hard line would not mean reckless use of military force in an already dangerous world. Instead, firmness mixed with moderation and caution. Not far from where Obama is now on this. And extremely far from Neoconservative notions that there is something cathartic, and affirming of America, in bombing the bad guys, regardless of the consequences

In parting, if you came across a pitiable student wholly unfamiliar with Leo Strauss, or his opponents and proponents, who had to give a brief synopsis of why Strauss is worth knowing, what would you tell them?

Strauss believed that we are all capable, if we use our reason and start confronting the present with the past, of becoming a little less the prisoners of our own emotions and prejudices, and those of our time and place. It will make us better human beings-and citizens. He said of Thucydides, true wisdom always issues in gentleness.

Leo Strauss: Man of Peace

Cambridge University Press

$30; available September 2014

[Photo credit: Abode of Chaos, via Flickr Commons]

Robert Howse is the Lloyd C. Nelson Professor of International Law at NYU Law School. He has taught at Harvard, the University of Paris I (Pantheon-Sorbonne), and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His publications include, with Bryan-Paul Frost, the translation of the interpretative essay for Alexandre Kojève’s Outline of a Phenomenology of Right and The Federal Vision: Legitimacy and Levels of Governance in the US and the EU, co-edited with Kalypso Nicolaidis, as well as several articles on 20th-century political thinkers, including Strauss, Kojève, and Schmitt.

Robert Howse is the Lloyd C. Nelson Professor of International Law at NYU Law School. He has taught at Harvard, the University of Paris I (Pantheon-Sorbonne), and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His publications include, with Bryan-Paul Frost, the translation of the interpretative essay for Alexandre Kojève’s Outline of a Phenomenology of Right and The Federal Vision: Legitimacy and Levels of Governance in the US and the EU, co-edited with Kalypso Nicolaidis, as well as several articles on 20th-century political thinkers, including Strauss, Kojève, and Schmitt.

Related Posts

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon discusses her new book, Ashley's War, as well as the challenges women face as they look to join and fight alongside U.S. Special Forces.

Journalist Thanassis Cambannis discusses his new book Once Upon A Revolution and elaborates on the missed opportunities of Tahrir Square, the military regime's...

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon discusses her new book, Ashley's War, as well as the challenges women face as they look to join and fight alongside U.S. Special Forces.

Journalist Thanassis Cambannis discusses his new book Once Upon A Revolution and elaborates on the missed opportunities of Tahrir Square, the military regime's...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Popular Posts

-

Is the Marine Corps Setting Women Up to Fail in Combat Roles?

February 18, 2015 -

Women in Combat: Can versus Should

August 10, 2015 -

The F-35 Was Built to Fight ISIS

October 13, 2014

Recent Comments

- buy cialas on line on Christopher Coker on Prospects for a Great Power War

- erectile on Russia’s NATO Expansion Myth

- search Grand Prairie auto insurance quotes on Christopher Coker on Prospects for a Great Power War

Cicero on Twitter

Arnold Isaacs reviews #VietThanhNguyen's book on how the #VietnamWar and its spillover conflicts are remembered. ciceromagazine.com/r…

Arnold Isaacs reviews #VietThanhNguyen's book on how the #VietnamWar and its spillover conflicts are remembered ciceromagazine.com/r…

@DanKaszeta @CarlDrott Definitely! It'd be great to see an article of yours on Cicero again.

Arnold Isaacs reviews Peter Bergen's "United States of Jihad" and Scott Shane's "Objective Troy" for Cicero Magazine ciceromagazine.com/r…

Arnold Isaacs looks at recent two books which are straight-talking about the realities of "homegrown terrorists" ciceromagazine.com/r…

Arnold Isaacs reviews Peter Bergen's "United States of Jihad" and Scott Shane's "Objective Troy" for Cicero Magazine ciceromagazine.com/r…

.@ChrisMMiller80 examines the nuclear weapons debate, how it could be achieved and whether it would be a good thing. ciceromagazine.com/f…

Blogroll

- Government Executive- Defense

- The Monkey Cage

- War on the Rocks

- Task and Purpose

- The Long War Journal

- Political Violence at a Glance

- Duck of Minerva

- Just Security

- Lawfare Blog

- Small Wars Journal

- Phase Zero

- Overt Action

- The Bridge

Tags

© Copyright 2016. All rights reserved.