Pierre Bienaime reviews Andrew Cockburn's new book, Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins, which questions the efficacy of drones in warfare.

- What’s Unusual About Today’s ‘Dual-Use’ Technologies?

- War in the Eyes of an Engineer

- America’s Blind Addiction to Armed Drones

- Jens David Ohlin on the War against International Law

- The Problem of Industrious Refugees

- Improving CBRN Forensics Can Stop War Crimes

- Why the Pentagon Needs a War on PowerPoint

- Managing ‘Mission Creep’ in the Fight Against ISIS

- No Country for Old White Men

- This Week in War

- We Need Defense Innovators More Than They Need Us

- ‘Intelligence Failures’ Are Inevitable. Get Over it

- Tsar of Tsars

- Time to Partner with Iran

- Can A ‘Freeze’ Work in Syria?

- Interests, Not Emotion, Should Guide Response to ISIS

- An Awkward Residue of War: Burn Pits and Human Waste

- Is Religion Inherently Violent?

- Does Transnistria Matter? To Russia, It May

- The ‘Secret Speech’ and Putin’s Cult of Personality

- Vladimir Putin is No Mystery

- Is there a Place for ‘Total War’ in the Modern World?

- Bridget Coggins on How States Are Born

- Can Corruption Lose Wars?

- Is the Marine Corps Setting Women Up to Fail in Combat Roles?

- When Allying with ‘Evil’ Makes Sense

- Fool Me Twice, Shame on Minsk

- Nicolaus Mills on Army-Navy Football, Vietnam, and Brotherhood in War

- Don’t Build A Berlin Wall in Ukraine

- Don’t Bring Back the Powell Doctrine

- Looking Beyond the Military for Leadership Models

- How to Defeat ISIS without Becoming Them

- This Week in War

- When America and Its Writers Knew War

- Show Me the Terrorists’ Money? Easier Said Than Done

- Islam’s Clash of Beliefs, As Seen From Modern Iran

- Using Social Psychology to Counter Terrorism

- Nothing Unjust About Using Snipers in War

- Jeff Bridoux on Democracy Promotion in the Post-9/11 Era

- Why Terrorists Do Not Need Territory

- American Snipers and ‘Just War’ Theory

- State of Disunion: America’s Lack of Strategy is its Own Greatest Threat

- Is Sri Lanka Ready Yet For Postwar Reconciliation?

- American Snipers are No Cowards

- ‘Devils’ Alliance': Moscow’s Pact with Hitler

- A Former U.S. Army Interrogator on Why Torture Doesn’t Work

- After Charlie Hebdo: Identity, Society, and National Security

- ‘Concrete Hell': Urban Warfare in the 20th Century

- Scott Horton on How Secrecy Erodes the Ability to Wage War

- The ‘Zero’ Conundrum of Countering Threats

- Should Intelligence Officers be ‘Hunters’ or ‘Gatherers’?

- Don’t Overhaul French Anti-terrorism

- On Charlie Hebdo, United We Fall?

- The Army’s Fixed Wing Future

- Only U.S. Courts Can Ensure America Will Not Torture Again

- ‘The Lost Battalion of TET': One Answer to the U.S. Army’s Dearth of Substantive ‘Classics’

- The Forgotten Invasion

- Time Makes Right Choice for Person of the Year, but Something is Missing

- Treating Infections, Fighting Insurgencies

- War and America’s Compromisers in Chief

- ‘Sitting Ducks': Move Carriers Out of the Gulf, into Mediterranean

- Failure of State: They Fired the Wrong Guy

- Free Speech, Self-Censorship, and the Cartoon that Shook the World

- The Case for Coalitions of the Unwilling

- The Politics of Human Security

- American Grand Strategy or Grand Illusion?

- National Security Policymakers—No Experience Necessary?

- The Long Gray Online

- How Military Advisers Can Avoid Mission Creep in Iraq

- Rethinking the Role of Religion in Counterinsurgency

- American Witnesses of the Nazi Rise to Power

- CBRN Robotics: Unmanned Recon and Decon Systems Needed

- Iran Nuclear Talks a Win-Win for Tehran, Washington

- What the War Classics Teach Us about Fighting Terrorists

- When Politics and Intelligence Meet

- Revisiting the First 102 Days of the War on Terror

- A New and Personal Narrative of Who Lost Vietnam

- Why ‘Military Readiness’ is so Vital

- Network-Centric Warfare Set the Stage for Cyberwar

- A Soldier’s Best Friend

- Why We Haven’t Felt the Full Effect of Sequestration — Yet

- Asymmetric Warfare and Abnormal Methodology: Redefining Victory

- The White House Must Change its ISIS Strategy

- Camp David and Goliath: The Triumph of Farsighted Peacemaking

- Ron Capps on PTSD and Recovery from Serving in Five Wars in Ten Years

- President Bush is Still Wrong on Iraq

- Tales from Kabul’s Gender-Bending Underground

- Size of U.S. Army Should be Determined by Needs of Victory

- What Was a Russian Sub (Possibly) Doing in Swedish Waters?

- Ottawa’s Lone Gunman Shows Weakness of ISIS

- The Lives of ‘Others': Menachem Klein on Healing Israel’s Divisions

- Is ‘Restraint’ a Realistic Grand Strategy?

- On Integrity: The Foundation of Leadership

- The Case for Arming Rebels

- ‘Friction’ Where U.S. Intelligence and Policymakers Meet

- A Trail of UN Malfeasance in Afghanistan

- The F-22 Over Syria: Efficiency and Effectiveness

- The F-35 Was Built to Fight ISIS

- Bing West on Fighting the ‘Forgotten War’ in Afghanistan

- Military Adaptive Leadership: Overcome or Overcompensate?

- The Lows and Highs of Life Aboard an Aircraft Carrier

- Can Drones Help Us Clear ISIS-Controlled Cities?

- To Defeat ISIS, Change the Balance on the Ground

- Paul Staniland on How to Fix Counterinsurgency

- How Risk of Great Power War Could Reshape Energy Security

- On Food, Wine, and War

- Limp into Iraq, Limp Out: Time to Revive the ‘Powell Doctrine’?

- Asymmetric Warfare Goes Both Ways

- Leo Strauss: Teacher, Philosopher, ‘Man of Peace’?

- Can a Divided UN Help us Fight Terrorism?

- Time to Take Chemical Weapons More Seriously

- How to Assess Risk in a World of Threats like ISIS

- Is COIN No Longer Relevant?

- We Still Need to Defeat Assad, Not Just ISIS

- Helen Thorpe on War, Sex, and the Women Who Serve

- The Necessary Hypocrisy of Torture

- Send Development Aid to North Africa, Not Drones

- What the War with ISIS Teaches Us About Strategy

- Time for another ‘Sunni Awakening’ in Iraq

- With Russia, Eyeball to Eyeball Again

- A Witness to Britain’s War Crimes in Kenya

- A Review of Rory Kennedy’s ‘Last Days in Vietnam’

- Is a New ‘Holy Alliance’ Forming in the Middle East?

- Why a War of Attrition Favors Us, Not ISIS

- Do Insurgents Benefit from Controlling Territory?

- Full-Spectrum Engagement: Better than War

- It Takes A Massacre to Save a Village

- Laura Kasinof on Being an ‘Accidental War Correspondent’

- Sorry Realists. ‘Containment’ Won’t Work Against ISIS

- For Refugees in Turkey, A Tipping Point Looms

- Would Cicero Have Approved of Putin’s War in Ukraine?

- In Iraq, A Faustian Bargain Awaits

- Ruti Teitel on Why Power is Shifting in International Law

- For the Future Force, More is Not Always Better

- For Russia, Death by a Thousand Aid Convoys

- Unfinished Wars a Recipe for Unsuccessful Nation Building

- Is Extremist Hip Hop Helping ISIS?

- Anjan Sundaram on Life as a ‘Stringer’ in the Congo

- How to Found a New Iraq From Embers of War

- Let Iran and ISIS Fight It Out

- Nicholas Seeley on Rumors, Love and War in a Syrian Refugee Camp

- Military Force Structure Math-the American Way

- Why ISIS is More Dangerous than Al-Qaeda

- How Do We Protect the Kurds? Like We Did in 1991

- Spymaster Jack Devine on Building a Better CIA

- Time to Retire GWOT Mindset in Africa

- A Falklands Strategy to Avoid War over Spratleys

- What the Air Force Can Learn from FedEx

- Is ‘Wartime’ Conceptually Different From Peacetime?

- Kayla Williams on PTSD, Recovery, and Life After War

- Joshua Rovner on Iraq and the Politics of Intelligence

- The Future of America’s All-Volunteer Force

- It is Time to Retire ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’

- The ‘July Crisis': WWI Lessons for Gaza, Ukraine, and Iraq

- Russell Crandall on COIN and America’s Dirty Wars

- Is Defeating Guerrillas Really All About Good PR?

- Prelude to Another Russian Missile Crisis

- A Cure For America’s ‘Iraq Syndrome’

- Ahron Bregman on Gaza, Israel, and Palestine

- Germany-U.S. Spy Scandal: Typewriters & Intelligence

- Getting Behind ‘Hybrid’ Warfare

- Voices of Pashtun Women from Wartime Afghanistan

- What 1914 Teaches Us About Naval Warfare Today

- Revisiting COIN Strategies in Vietnam

- Kristan Stoddart on U.S.-NATO Nuclear Policy

- How War Has Shaped American Exceptionalism

- The Chemical Fingerprint of Assad’s War Crimes

- Cold War Lessons for Counterintelligence Today

- Is Iraqi Kurdistan on the Verge of Statehood?

- ‘Everyday’ Ways to Fix Peacekeeping

- The ‘Hot’ War in Cold War Southeast Asia

- Taming Cities of the 21st Century: A Book Review

- Ian Morris on Why War Is ‘Sometimes Good’

- ‘The Troubles': COIN Tactics Against the IRA

- The Myth of Obama’s Realism

- Why Urban Warfare Studies Still Matter

- Will U.S. Military Advisers Face ‘Mission Creep’ in Iraq?

- Christopher Coker on Prospects for a Great Power War

- Two Views of Intelligence

- Just Killers, Moral Injuries

- Are Manned or Unmanned Aircraft Better on the Battlefield?

- The Fading Memory of War in Congress

- The U.S.-Chinese War Over Africa

- Russia’s Fair Energy Friends

- Moral Injury and Military Suicide

- Moral Injury and the American Soldier

- Russia’s NATO Expansion Myth

- Morten Ender on Millennials and the Military

- How Many Fingers in the Warthog Pie?

- What a ‘Head Strong’ Military Looks Like

- Ireland 1916-1921: The War COIN Theorists Forgot

Narrative history is a kaleidoscope. A byproduct of 19th century experiments into light polarization, kaleidoscopes operate on the theory of multiple reflection. In practical terms, when a viewer looks into and rotates the cylinder, they “see” refracted light illuminating an array of multicolored beads. That light is then reflected against three mirrors that yield seven duplicate images. What is really a mishmash of light, refraction and reflection appears to the human eye as a series of symmetrical shapes and images. Using words instead of beads, historians also make order out of chaos; in this way, Lawrence Wright is a master kaleidoscopist.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Wright is equal parts writer, artist, and serious political thinker. His newest work, Thirteen Days in September, required all three traits. This book is simultaneously a history of the modern Middle East, a master portrait of political personalities, and a prescription for peacemaking. It is also a storytelling tour de force.

In the strictest terms of objective reality, narrative history is to “fact” what a kaleidoscope is to “image perception.” In both cases, the human mind imposes a “false” symmetry on what are utterly arbitrary and random phenomena. Postmodernists would certainly agree. To them, attempts to impose one uniform narrative upon multiple storylines represent a reductionist fantasy that deceives both author and audience.

The postmodernist critique of mainstream, narrative history is a straw man. No sophisticated narrative historian would ever proclaim his or her work constituted an utter, total truth. In an attempt to sketch an account that both writer and reader can ascertain, the historian imposes order upon the chaos that is reality. Indeed, Herodotus implicitly understood what neuro-humanists only beginning to discover. The brain seeks order from chaos, prefers symmetry to asymmetry, and demands meaning as opposed to nihilism. Insights from the burgeoning field of neuro-humanities reveal that the brain, not hegemonic cultural masters, wants, nay demands, classical, literary forms. From a child peering into a kaleidoscope to Lawrence Wright depicting Camp David, the mind’s imposition of order and symmetry onto natural and human phenomena are both false and wholly necessary.

Never is the recognition of narrative history’s falsehood and utter necessity more pertinent than in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Both sides incessantly proclaim the existence of “multiple narratives.” In this way, a Palestinian emphasizes an IDF massacre not a PLO slaughter (and vice-versa). Indeed, multiple narratives is a fancy, grownup way of saying, “My story and my perspective are the ones that count.” Our realities and mythologies, however, inevitably collide. Certainly, we all bring a “multiple” (or unique) narrative with us every time we interact with another human being. Humans, however, can only coexist when they bend their unique understandings of the world and allow for plural truths and realities.

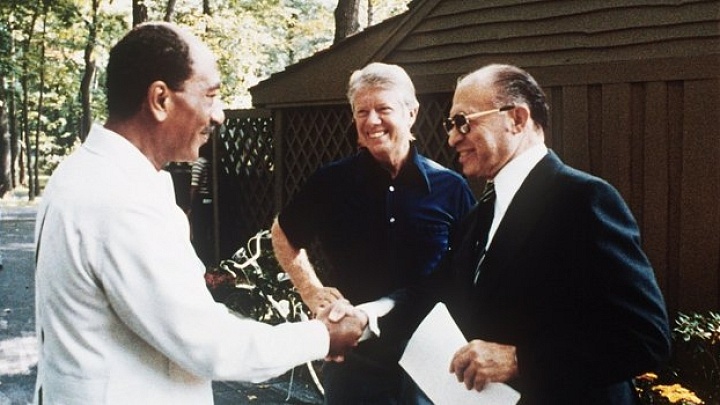

In September 1978, Jimmy Carter, Anwar Sadat, and Menachem Begin brought their multiple narratives to a diplomatic summit. Wright’s gripping account reveals the history, drama, promise, and tragedy of those fateful thirteen days. In his book, the author depicts those multiple narratives and how Sadat and Begin haltingly moved toward pluralism. The foundation of diverse, democratic societies, pluralism is a scarce commodity in the Middle East. Indeed, Sunni Islam’s demographic, political, and social domination of the region has bequeathed a society profoundly hostile to engagement, encounter, and dialogue with alternative worldviews.

The Middle East is a complicated and diverse region. Americans, however, don’t care. Jimmy Carter risked his presidency for peace due to his interest in the Holy Land. The Holy Land happens to also feature the Middle East’s most nagging geopolitical problem: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The State of Israel’s creation spawned a nasty, ongoing war over real estate dear to each branch of the Abrahamic faith. In the process of creating a state, the Israelies unwittingly spawned secular terror, the PLO, religious nihilism, al-Qaeda, ISIS, and an Arab-Israeli conflict that has frozen the region’s geopolitics in 1948.

To Wright, an Israeli-Palestinian accord remains the keystone to solving the region’s turmoil. In this way, the author understands the region from a very American perspective. To be sure, ending this conflict would surely solve many of the Middle East’s woes. But the long war that is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is just as much symptom than cause. The region’s fundamental hostility to pluralism, not the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, accounts for many of its developmental woes.

Though Wright overestimates the Israeli-Palestinian conflict’s importance, Thirteen Days in September remains an important book. The Camp David Accord’s basic narrative has been told many times before, but not in such a masterful way. Using the thirteen days of Camp David peace talks as his work’s narrative spine, Wright devotes one chapter to each day. In this way, he carries the reader back into September 1978.

Never is the recognition of narrative history’s falsehood and utter necessity more pertinent than in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Both sides incessantly proclaim the existence of “multiple narratives.”

This is not a blow-by-blow account of the peacemaking process. Writing in the grand tradition of master historical narratives, Wright details the major players. In the midst of his chronological account, he launches into asides in which he gives historical background to the region’s geopolitics and the biographies of Carter, Begin, Sadat and their respective aides. Through this, the author recreates for the reader the hermetically sealed world that was Camp David in September 1978 — a world in which each major player brought their own history and versions thereof to the negotiating table.

A masterful storyteller, Wright employs his clever 13-day narrative device for more than aesthetic reasons. He rightly considers the accords, for all of their shortcomings, a remarkable achievement in peacemaking. By myopically focusing upon those days, he argues and proves, that peace is achieved by human beings, “prejudiced by their backgrounds, hampered by domestic politics, and blinded by their beliefs.”

Rightfully pilloried for a lackluster presidency, in this book Carter emerges as a farsighted peacemaker. Indeed, Wright credits the president’s very political weakness, a fixation on minutiae, for ensuring success at Camp David. With laser focus and bulldog intensity, the president cajoled, threatened, begged, and otherwise prodded Begin and Sadat into a peace deal both desired but could not achieve on their own.

Largely forgotten by history and obscured by a cavalcade of feckless successors, Anwar Sadat comes to life. In Wright’s lively prose, Sadat reemerges as a gambling, impulsive, far-sighted, and ultimately heroic figure. Out to displace Israel as America’s primary ally in the region, Sadat came to Camp David with a sophisticated geopolitical strategy and a negotiating team united in their opposition to the accords. If Carter deserves “gold,” then, to the author, Sadat warrants the “silver” for his ability to overcome history and choose peace.

Of the three, Begin emerges as the most tortured leader. Wright paints the painful portrait of a young Polish Jew who endured a cruel, anti-Semitic society and by an accident of history escaped the Holocaust. As an adult, Begin emerged from the ranks of a shadowy and vaguely anti-Arab Irgun to found the right wing Likud Party and become the first non-Labour Prime Minister of Israel. Surrounded by aides less burdened by the past, Begin grudgingly and haltingly yielded to Carter’s threats and demands and signed the Accords.

Thirteen Days in September is timely. It is a prescription for peacemaking. An end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has never seen so remote. Wright’s work stands as an explicit reminder that peace is possible through unyielding American leadership and an Arab and Israeli willingness to embrace pluralism.

[Photo: AFP/Getty Images]

Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David

by Lawrence Wright

Alfred A. Knopf, 368 pages. $27.95 (cloth)

Jeffrey Bloodworth is an associate professor of history at Gannon University. He is the author of The Wilderness Years: A History of American Liberalism, 1968-1992.

Related Posts

Is Religion Inherently Violent?

Jason KlocekFebruary 273

UC Berkeley's Jason Klocek reviews Karen Armstrong's Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence in which she seeks to systematically debunk the...

Arnold Isaacs reviews Nazila Fathi's new memoir, The Lonely War: One Woman's Account of the Struggle for Modern Iran, in which she explores the Islamic...

Is Religion Inherently Violent?

Jason KlocekFebruary 273

UC Berkeley's Jason Klocek reviews Karen Armstrong's Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence in which she seeks to systematically debunk the...

Arnold Isaacs reviews Nazila Fathi's new memoir, The Lonely War: One Woman's Account of the Struggle for Modern Iran, in which she explores the Islamic...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Popular Posts

-

Is the Marine Corps Setting Women Up to Fail in Combat Roles?

February 18, 2015 -

The F-35 Was Built to Fight ISIS

October 13, 2014 -

President Bush is Still Wrong on Iraq

October 29, 2014

Recent Comments

- Weekend Reading List: March 27-29 Edition on War in the Eyes of an Engineer

- strategicservice on America’s Blind Addiction to Armed Drones

- peter38abc on America’s Blind Addiction to Armed Drones

Tags

Blogroll

- No RSS Addresses are entered to your links in the Links SubPanel, therefore no items can be shown!

Cicero on Twitter

@ClintHinote writes that U.S. #military should embrace “dual-use” technologies that help us to fight better. ciceromagazine.com/opinion/whats-…

11 hours agoRT @clareoneill: Use of Force in UN Peacekeeping Operations: Problems and Prospects tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10… @warstudies @RUSI_org @DavidUcko

3 days agoRT @MaloneySuzanne: Interesting piece on religion as an advantage in negotiations ti.me/1btyMfp Except Iran's nuke pursuit isn't m…

5 days ago

© Copyright 2015. All rights reserved.

One Comment