As the U.S. involvement in Afghanistan tapers and military attention shifts to more pressing theatres, the women of Afghanistan brace themselves. They are exquisitely aware that militant groups are poised to escalate their activities, which would undoubtedly lead to regrettable setbacks in the impressive gains that Afghan women have made in the last decade. Women may lose the opportunities for education and engagement in the public sphere – advances that continue to be hard-earned and inconsistent. The challenges of being a woman in Afghanistan can be illustrated by studying the centuries-old tradition of converting young girls to boys, a creative solution to a complex problem.

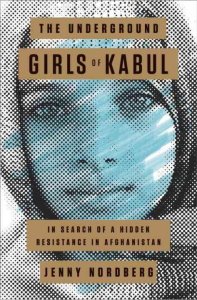

Swedish journalist Jenny Nordberg spent months at a time in Afghanistan, getting to know the valiant, gender-defying women she describes as “The Underground Girls of Kabul.” Nordberg’s book, an insightful cross between journalism and anthropology, centers on the Afghan bacha posh, a girl dressed as a boy. The custom fills needs created by a patriarchal society that values sons over daughters. The book is a fleshed out version of her 2010 New York Times article, a piece that spotlighted the bacha posh daughter of an Afghan female parliamentarian, Azita.

Swedish journalist Jenny Nordberg spent months at a time in Afghanistan, getting to know the valiant, gender-defying women she describes as “The Underground Girls of Kabul.” Nordberg’s book, an insightful cross between journalism and anthropology, centers on the Afghan bacha posh, a girl dressed as a boy. The custom fills needs created by a patriarchal society that values sons over daughters. The book is a fleshed out version of her 2010 New York Times article, a piece that spotlighted the bacha posh daughter of an Afghan female parliamentarian, Azita.

Azita’s story is the story of Afghanistan’s women. She is the hardworking and determined second wife to a man she had no interest in marrying. She is relatively well educated compared to the provincial first wife who has internalized the misogyny of Afghan society. Azita, with her involvement in parliament, sees first-hand the corruption that debilitates the government and confounds the work of non-governmental organizations. She is the former bacha posh who has made her daughter into a son and wonders if she has done the right thing. By the end of the book, she is the canary in the coal mine. She has lost her seat in parliament and her husband has resumed physically abusing her.

Nordberg treats her subjects as whole persons, delving into the impact the gender-bending practice has on their psychological well-being, their interpersonal relationships and their aspirations.

Nordberg’s ethnographic work faces the challenge most anyone would have in researching a topic that cuts so close to the interviewer. It is, she states, her subjective account and must be, for a Western woman would be hard-pressed not to inject a bit of bias into her field study in Afghanistan, a country infamous for its treatment of women. While the reader hears her opinions loud and clear, she does well to play devil’s advocate along the way, challenging the notion that the gender disparity she finds is unique to Afghanistan. She points to places and times throughout history where women have shared such a subjugated status. Nordberg reminds us of just how recently women gained basic rights even in the western world. In this way, she broadens her focus beyond Afghan borders and makes the book a touchstone for discussion about the challenges of being a woman worldwide and about the very construct of gender.

Nordberg treats her subjects as whole persons, delving into the impact the gender-bending practice has on their psychological well-being, their interpersonal relationships and their aspirations. With the tenderness of a friend, she shares their sometimes painful and sometimes triumphant narratives with the reader. The connection she has developed with these individuals is obvious in the way she writes on some of their more intimate exchanges. She is privy to the bruises a wife suffers at the hands of her husband, the tears of a regretful father, and the ring one woman wears daily- a gift from a man other than her spouse. She tells us of the former bacha posh who learns of her husband’s infidelities and the fear of becoming of divorcee – it is not the dissolution of the marriage she laments, but rather the knowledge that her children will likely be taken from her while she is branded a failed wife. These are the aspects of Afghan society that make women yearn for the life of a man. In a place where private matters are not spoken of readily, Nordberg had to work diligently to gain the trust of her interviewees.

Nordberg does not shy away from asking the tough questions, touching on taboo subjects like sex and love. Her illuminating inquiry reveals the dearth of knowledge among the country’s men and women in matters related to sex, from basic anatomy to the mechanics of consummating a marriage. Even some of the more educated favor superstition over science and ascribe to what can be considered “old wives tales.” It is against this backdrop of ignorance that women can easily be manipulated and controlled.

Where Nordberg may ruffle feathers is in the use of charged terms like “uncover,” “discover,” and “broke the story” when describing her connection to the bacha posh custom. The sensationalism of “secret” and “underground” is not lost on the reader, though it seems incongruous to the Afghan who knows the bacha posh practice is one overtly accepted by society. The girls and women she describes are part of a charade the entire community tolerates, as we see in her stories. It is an unnecessary Columbus-like claim that distracts from her poignant research and the sensitivity with which she handles her female subjects and their family dynamics.

Nordberg paints a vivid picture of the daily life of Afghan women, detailing the nuances of their trips to the market, workplace dynamics and slavery to the almighty “reputation.” She introduces the opinions of researchers like Nancy Dupree and others who have worked in Afghanistan. Nordberg shows the effects of the political climate on Afghan women over the course of its history. In more peaceful times, Afghan women enjoyed a sophisticated life with freedoms similar to the western world. She concisely chronicles the rise and fall of women’s rights in the context of the many regime turnovers and the failed Soviet takeover that destabilized the country for decades.

Nordberg wisely points out that the many well-intentioned foreign aid groups, humanitarian organizations, and development projects may have made only transient gains for Afghan women’s rights, as they are sometimes seen as having “Western-backed” agendas. “Men are the key to infiltrating and subverting the patriarchy,” she writes. “Those hundreds of ‘gender projects’ funded by aid money might have been more effective if they had also included men.”

She speaks with the wisdom of one who realizes true and enduring change, a sustainable takedown of the patriarchy, must come from within.

[Photo source: Flickr Commons]

The Underground Girls of Kabul

by Jenny Nordberg

Crown, 368 pages, $15.62

Nadia Hashimi is the author of the new novel, The Pearl that Broke its Shell. Her parents left Afghanistan in the 1970s, before the Soviet invasion. In 2002, Hashimi visited Afghanistan for the first time. She lives with her family in suburban Washington, D.C., where she works as a pediatrician.